After the Liang Hui: Team Xi in Charge

"Heaven is looking at what humans are doing. The firmament has eyes" (人在干,天在看,苍天有眼). These were Premier Li Keqiang’s parting words for his colleagues in the State Council, China’s cabinet. This year’s meeting of the National People’s Congress, China’s Parliament, which ended on March 13, suggests that the eyes of heaven are the only accountability left for China’s now third term president Xi Jinping, the general secretary of the Communist Party of China (CPC). Xi received 2952 votes out of the 2952 NPC delegates present.

Li Keqiang showed no special emotion while presenting his 10th and last government work report. His somewhat stiff public persona had always contrasted with his lively, inquisitive manner in more private settings. The report itself was uneventful and blissfully short at 53 minutes in all. After his speech, he bowed to the audience, to the rostrum with the new party leadership, and to the audience again, and sat down. This marked the end of his career as a government official.

Even though he was overshadowed by Xi Jinping in the past decade, Li Keqiang, a one-time contender for the CPC top job, can look back on an exceptional career. As a graduate from the famous “Class of 77,” the first class of university graduates that passed the university entry exam after the cultural revolution, his career was on a fast track, supported by his growing powerbase in the Communist Youth League.

He became the youngest party secretary in CPC history in Henan, and later in Liaoning, before becoming executive vice-premier under Premier Wen Jiabao. As such he led China’s economy through the global financial crisis, and initiated a plan to steer China away from the middle-income trap. The plan inspired Xi Jinping’s first economic program in 2013, the one that promised a “decisive role of the market,” and was cheered by the market at the time. LI Keqiang was also the father of “mass entrepreneurship” launched in 2014, which resulted in millions of new business registrations.

Times have changed, and the 2013 plan was gradually abandoned and overshadowed by Xi-nonomics, which emphasises the role of the state and national security over that of the private sector. Development is still the primary task of the party, but “Security is the bedrock of development, while stability is a prerequisite for prosperity" Xi said in his closing speech for this year’s NPC.

The government work report.

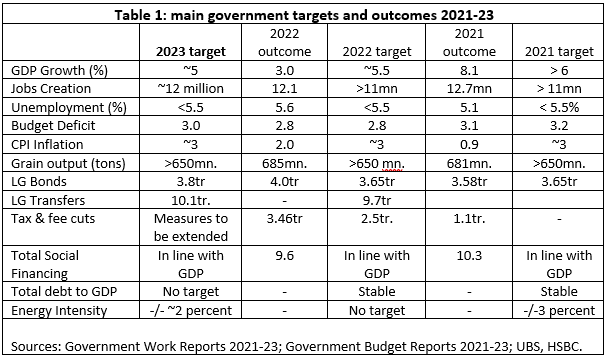

This year’s indicative target for GDP growth (table 1) was a modest “around 5 percent” which was decidedly unambitious, perhaps reflecting caution after the government royally missed the 5.5 percent target of last year. The slightly higher target for new jobs creation at 12 million (11 million last year) shows the government’s concern with rising unemployment, especially among the youth. This year, some 15 million people will join the workforce, 11.6 million of which have a university degree, and they have had a hard time finding jobs in the past 2 years.

The government will only modestly stimulate growth, though. The announced government budget deficit, at a headline 3 percent, was the same as last year—though the total deficit is more like 8.5 percent of GDP, not counting off-budget activities of local government. Total Social Financing, a measure for monetary policy, is like last year planned to be in line with GDP growth, thus stabilizing debt levels as a share of GDP at the very high levels reached after years of credit-fuelled growth.

The government’s short-term policy priorities are familiar as well: expanding domestic demand, modernize the industrial system, support public and private sector alike, attract more FDI, contain economic and financial risks, and further transition to a green economy. On the latter, the return of a target for reduction in energy intensity (by 2 percent) is encouraging, as it was dropped after energy shortages in 2021 and amid the COVID-19 downturn. In his speech to the NPC, Li Keqiang took little time to elaborate on these priorities—it is up to the new team to make these work.

Team Xi

Team Xi has taken over all the key posts in government and legislature, including those of premier (Li Qiang), executive Vice Premier (Ding Xuexiang), Vice Premier in charge of the economy (He Lifeng), Chairman of the National People’s Congress (Zhao Lijie) and the People Political Consultative Congress (CPPCC) (Wang Huning).

Aside from Premier, Vice Premiers and State Councillors, most of the ordinary ministers were reappointed. The reappointment of Finance Minister Liu Kun and Central Bank (PBC) Governor Yi Gang came as a surprise, as they had lost their position in the CPC Central Committee last fall, which usually is a good indicator for retirement. On balance, this continuity is good news, especially because it preserves the international experience the two have build up in the past several years, including through meetings at the G-20, IMF and World Bank meetings, and the Bank for International Settlement.

For the PBC, this could mean that the agendas of internationalization of the RMB and gradually opening of the capital account are still on the books. The former has become more relevant for China and its trading partners, as they perceive an increasing “weaponization” of the dollar. Whether it bodes well for fiscal reforms remains to be seen, as over the past several years the incumbent minister has shown little appetite for the major fiscal reforms needed to support a new growth agenda. These reforms, put in motion by former Finance Minister Lou Jiwei in 2014, have lost momentum since, and some have gone in reverse.

Women may hold up half the sky, as Mao Zedong famously said. In today’s China, though, they are far from holding half the minister-level appointments, though: of the 34 ministers and State Councillors, only 3 are women. For the first time in decades there were no female vice premiers appointed, and only one female State Councillor, Shen Yiqin, the former party chief of Guizhou province. This makes her the most senior woman in the Party-State as no women were appointed to the 24 men CPC politburo last year either.

Party and Government

These personnel changes in cabinet mattered less than those made last October in China’s true halls of power, the CPC Politburo and its Standing Committee. More than ever before, under Xi Jinping it is the Party that controls the government, and is increasingly replacing government in operational matters as well, through its growing number of Committees and small leading groups.

This is full circle from the reforms that Deng Xiaoping initiated in the 1980s, which aimed to bring more separation of government and party. There was never any doubt that the Party was in charge—the “Four Cardinal Principles” were the bedrock of even the most fervent reforms.

Separation of party and state allowed the former to focus on political directions, while leaving the formulation and administration of policy to a government staffed with technocrats. This created an accountability of sorts, but this separation of power, no matter how subtle, was too much for Xi Jinping, who wants “the Party to lead everything.”

The new premier, Li Qiang, was on message. In his first press conference, traditionally held after the closing of the NPC, he said that his main priority was to “turn the beautiful blueprint” that general secretary Xi had laid out at the20th Party Congress into reality. The short-term challenges, he said, were as defined by the Party’s Central Economic Work Conference, with a focus on maintaining stability, while making progress on quality development.

The NPC also approved several changes to the organization of government. These were pre-approved by the second plenary of the 20th CPC Central Committee that ended a few days before the NPC opened, but they seem less sweeping than the 2018 government reforms.

The major ones seem to make sense: a centralization of financial sector supervision in a new state agency, and repurposing the Ministry of Science and Technology from an implementer to a funder and policy maker for research and development. Other ministries, National Laboratories, Universities, and companies should implement the policies to achieve indigenous innovation.

In apparent contradiction to the desire to reign in the financial sector, the PBC is to abolish its 9 supra-regional branches and county-level offices, and revert to provincial level branches. Such a structure caused problems in the past as provincial (and municipal) governments saw the PBC branches as their own piggybanks until the mid-1990s. Some fear that the move could undermine the independence of the PBC, though that independence was never close to that of OECD country central banks anyway.

The new National Data Bureau under the NDRC aims to realize China’s ambitious vision for data as a new factor of production. This is quite a task and it remains to be seen whether the Bureau can succeed. If it does, China will have set a very different course from the western world, where data is still largely gathered, curated and used by private companies.

The approved cut of central government staff by 5 percent, and the alignment of the salaries in the financial supervisors with civil service salaries (which is a major salary cut for the former) may bode less well for government capacity. Ever since Zhu Rongji cut the ranks of central civil servants in half the centre has been struggling with understaffing. The implication is that important tasks such as preparing new policies or supervising local governments are short-staffed. The plan may be to leave this to the party as well.

The approved government reforms are only half the picture. In the coming weeks, changes to the party structure are to be announced, matching those of government. In 2018, it was the party changes that reinforced the party control over government, and this year could be the same.

Rumours have it that a revamp of the Central Finance Working Group is in the making. That group prepared the major financial sector reforms in 1998-2002, including a recapitalization of the banking system. This could signal that major financial sector reforms are ahead, signals amplified by the rumoured appointment of He Lifeng as PBC’s Party Secretary.

Law on Legislation

A widely debated piece of legislation was the Law on Legislation. The amendments, which were duly passed by the NPC are in part cosmetic: every law must now include a revised preamble that incorporates "advancing the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation on all fronts" through "a Chinese path to modernization" which is part of Xi Jinping’s Thoughts. Earlier drafts had apparently deleted "reform and opening to the outside world" and "taking economic development as the central task" from the preamble, but they were brought back into the final version. Of course, the revision adds "Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era" as a guiding principle for law making.

The more substantive part concerned opening a process for emergency legislation. This route would allow for a single reading by the NPC standing committee of proposed legislation in case of emergencies, instead of the usual 3. This raised some eyebrows internationally, and some saw this as yet another means by which China could sideline the legislators, while others saw emergencies on Taiwan as the real target. However, the fast-track legislative process is not much different from the existing arrangements in which the Standing Committee of the NPC can approve temporary legislation when needed.

On the plus side of the balance, the consultation mechanisms for draft laws were expanded, and the number of local legislative consultation offices would be expanded.

The Party and the Private Sector

How China conceives the role of the private sector going forward remains crucial for growth. After all, it is the private sector that produces more than 60 percent of output and more than 80 percent of employment. Since Jiang Zemin’s “Three Represents” the private sector had also been embraced by the CPC. But the past few years have not been kind to private enterprises: in addition to the COVID-19 policies, talk of “controlling the barbaric expansion of capital” and the regulatory crackdown on internet companies had shaken the confidence of the private sector.

Li Qiang is on a mission to restore that confidence.

During his time in Zhejiang, Jiangsu, and Shanghai, Li Qiang has been a strong supporter of the private sector and even civil society. “There should be more Alibabas and more Jack Ma’s” he had said in 2014. Even more remarkably: “The government cannot be an unlimited government,” he said in 2015, “to build a limited yet effective modern government, you need to transfer a lot of managerial power to social organisations.”

That was then, this is now. In his post-NPC press conference, Li Qiang dutifully referred extensively to party policies and guidance (sometimes checking notes on them) but overall he gave the impression he was confident and in full command of the substance of questions ranging from the economy to Taiwan to US-China tensions.

Li Qiang did expressed continued support for the private sector, though: “I believe private entrepreneurs will make more splendid entrepreneurial story in the new era” he said, and that “the two ‘unswervings’ and important part of China’s basic economic system. This policy will not change” The “two unswerving” refers to support for both the public and the private sector.

Li Qiang also said that there had been “inappropriate discussions” on the role of the private sector last year—perhaps referring to some zealous party members that had posed it was time to abolish the private sector altogether. “Entrepreneurs will enjoy a better environment and broader space in the new era” Li Qiang said at the press conference.

Xi Jinping had taken a similar line in a meeting with private sector representatives to the CPPCC on March 7. “The Party Central Committee has always insisted on "two unswervings" and "three unchanged", Xi Jinping said. He added that “It is necessary to guide private enterprises and private entrepreneurs to correctly understand the principles and policies of the Party Central Committee.”

The question is how overbearing this guidance will be.