China as number 3?

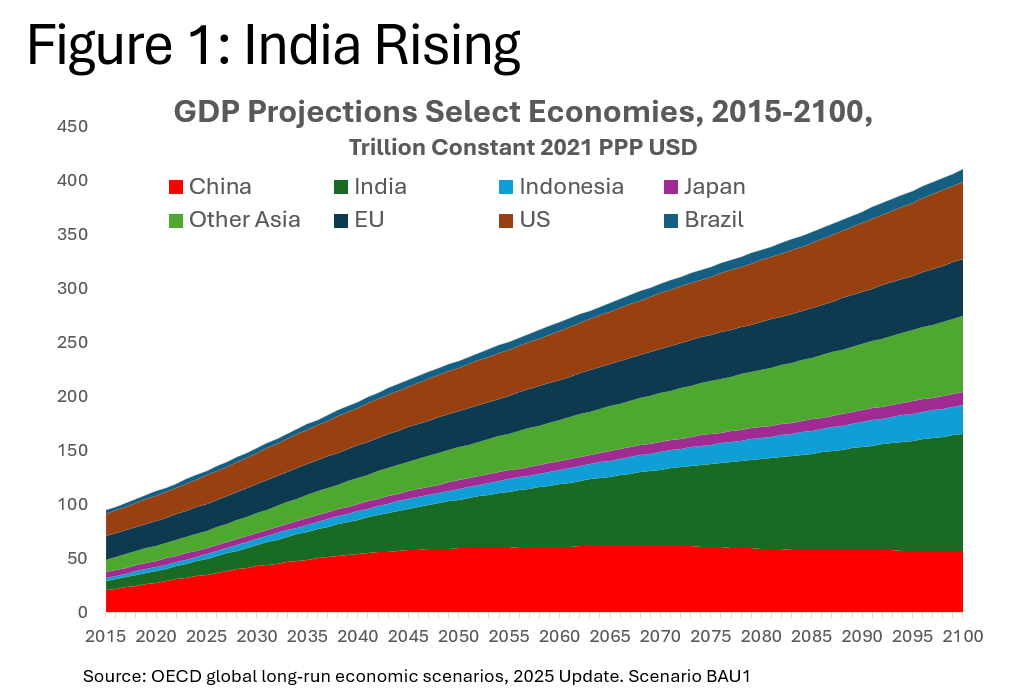

India may be the largest economy in the world by the end of the century, and the US could be second.

The latest OECD long term scenarios, released without much fanfare in September last year, suggest that India will overtake be the largest economy by the 2060, and will be almost twice the size of China by the end of the century (Figure 1). The USA, which is currently in second place, will slip to third place in the 2040s, but then catch up with China again in the 2070s, two centuries after it first overtook China to become the largest economy in the world in the 1870s. In the previous OECD scenarios released in 2023, the projection horizon was the year 2060, and China was then projected to still be the largest economy by then with a considerable margin. This is still just the case in the current projections, but the big changes occur in the second part of this century.

What has changed?

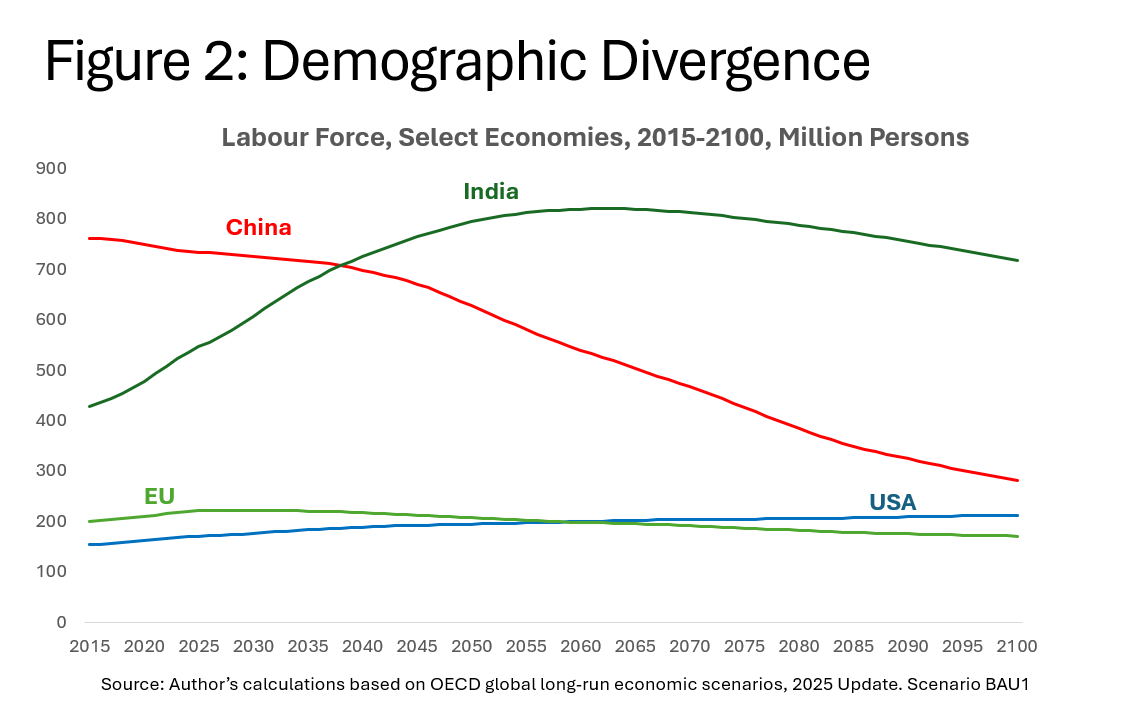

It is largely the changed demographics that make China slide in the ranks of GDP. With the new UN Population Division projections released in 2024, China’s population declines much faster than expected before, with most of the decline in the second half of the century. The median projection puts China’s population at some 650 million people by 2100. Even with a rise in labour force participation, China’s labour force, according to the scenarios, will be less than 300 million by the year 2100, and barely 40 percent of that of India, and not that much larger than the United States (Figure 2). India will have the largest population in the world by far in 2100, having only started its decline by 2060. More so, labour force participation is expected to rapidly increase, from some 50 percent of the working age population (15-74 in the OECD projection) to some 70 percent by 2100. The US labour force, because of the country’s liberal immigration policies, also continues to expand, which is a key driver behind overtaking China again. However, is not just population dynamics that makes India surge and China lag behind.

The mechanics of the OECD scenarios.

The OECD uses a fairly standard model for generating its scenarios. It uses a Cobb-Douglas function with constant returns to scale, and two production factors: labour and capital and global technical progress. Basically, the model predicts countries’ GDP to converge, but the rate of convergence depends on “effective” labour and initial capital/labour ratio. In a steady state, all countries would grow with the global rate of technical progress, but most countries are catching up with more advanced countries. Effective labour depends on a country’s institutional strength. This is highly stylized in the model, and measured by 3 factors: (historic) macroeconomic stability, rule of law[1], and economic openness,[2] which no doubt is somewhat arbitrary. Irrespective, the values are about the same for China and India, but India’s efficiency of labour grows faster, simply because it is further away from the frontier.

Another factor in convergence is capital stock dynamics. Due to the assumptions of the model (Cobb-Douglass, labour share of 67 percent), the ultimate capital output ratio is a given—at 3.4, according to the OECD. But since China has more capital per worker to start off with (and sees the number of workers decline over time, which increases the capital labour ratio), China gets less GDP growth than India from the same level of investment.

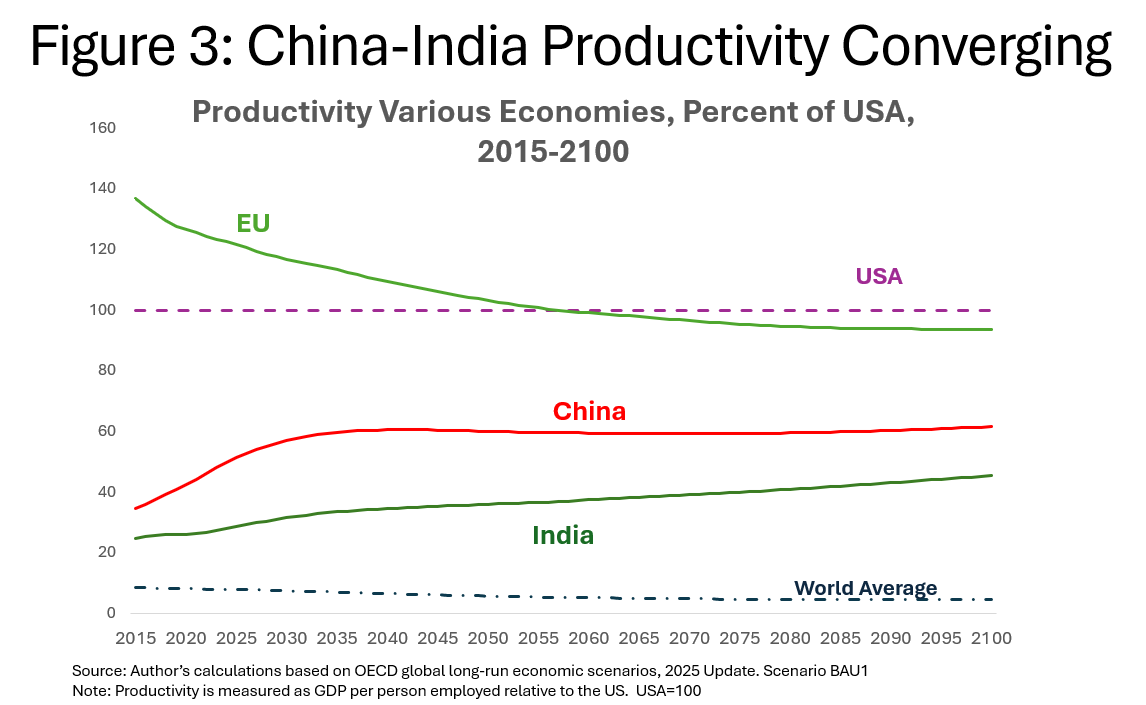

Productivity

Together, these factors explain why China’s productivity growth is lower than India’s (Figure 3). By Mid-century, according to the OECD scenario, China would even stop catching up with the USA, which still means productivity growth with about 1.3 percent per year. Productivity here is simply calculated (by yours truly) as GDP divided by the workforce. This is not a given, though. For instance, China could grow faster than the OECD scenario by “beating” the catch up rule in labour efficiency, say by applying AI and robotics faster than India and faster than the “frontier” country, the US. China may also grow faster if the share of labour stays below the level imposed by the model, which seems to be the case currently. China’s current policy orientation to boost consumption would, however, suggest that the labour share will rise over time.

The OECD scenarios are not destiny. Or to put it in the words of the OECD: “Long-run scenarios should not be treated as predictions of the future but rather as illustrations of some of the long-run challenges facing the global economy, how they might evolve, and how they might affect different countries.” (OECD, 2025, p.15). Nevertheless, demographics plays a big part, and India’s projected margin over China in size of GDP by the end of the century is very large, so it seems safe to say India will be the largest economy by then.

[1] based on the World Bank’s Rule of Law indicator

[2] the degree of economic globalisation is based on the KOF Swiss Institute’s economic globalisation index.

Didn't expect USA to catch up again. Is the demographic impact realy that strong?

Bert, I looked at global scenarios out to 2100 back in the early 2010s, and India came out at #1 in 3 out of 5. The US and China both came in at #1 once each. Here is the synopsis:

1. China will be the world’s largest economy for most of the time between its IMF forecast takeover of the USA in 2016 and mid century in every scenario, even the most pessimistic. However, it finishes the century at number one just once in the five scenarios, reaching

2100 in fourth place twice and second place twice.

2. India is the largest economy in the world in 2100 in three of the five scenarios and is a close second in another two. In four out of five scenarios India spends at least some time as the world’s largest economy.

3. The scenario that produces a world economic structure most consistent with a balance of power scenario (between the USA, Developed Europe, China and India) is one where emerging Asian economies collectively stall around the middle income level. This is also the scenario where the USA rallies back to number one by century’s end after falling behind in its middle decades.

4. Developed Europe finishes the century as the world’s third or fourth largest economy in each scenario, indicating that it will remain economically relevant even in the face of the Asian ascent.

5. While the Japanese will remain a wealthy people, the economy’s size will be surpassed in all scenarios by Indonesia, in most scenarios by Brazil and Russia, and on a single occasion each by Canada and the Philippines.

6. No economy outside the top four will comprise more than 6.1% of world output (a relative position equivalent to China circa 1996) in any scenario. What is highly notable outside the top four is that Indonesia finishes the century as number five in every scenario but one. That implies very strongly that the widely used BRIC grouping of countries is not a particularly useful one for long run analysis. These scenarios highlight that not only are China and India in a very

different league to Brazil and Russia, but also that Indonesia will be a bigger long run economic factor than either of the latter two powers.