After all the excitement of the “Two Sessions,” China’s annual festival of democracy, a less exciting, but possibly more important event took place in the week after. The Communist Party of China and the State Council together issued the “"Party and State Institutional Reform Plan." It is not exactly a ripping read, but the plan is crucial for understanding China’s priorities and institutional underpinning for policy priorities and actions for the coming years.

Among the changes in government and Party, the consolidation in control over technology policy stood out. The Party set up the “Central Science and Technology Commission” and the government reorganized the Ministry of Science and Technology. There is no doubt as to who is in charge: “The executive agency of the Central Science and Technology Commission is fully undertaken by the reorganized Ministry of Science and Technology.”

The new Party Commission aims to centralize leadership over science and technology, and consolidates the powers of 4 now-abolished leading groups in the field. The Ministry of Science and Technology is repurposed from an implementer to a funder and policymaker for research and development. Other ministries, national laboratories, universities and companies are to implement the policies to achieve China’s goal of indigenous innovation—i.e. less dependence on foreign technology.

This goal has become more urgent since the United States announced last October its measures to restrict China’s access to high-end semiconductors and the tools to make them. In the meantime, the Netherlands and Japan—two countries with critical capabilities in chipmaking—joined the US in its endeavour. Jake Sullivan, in his speech in September 2022 said that the goal of the US was to keep China back in absolute, nor relative terms in semiconductors and other critical technologies as I discussed elsewhere.

CPC General Secretary Xi Jinping left no doubt as to the importance of innovation in his work report at the 20th Congress of the CPC in October 2022, stating that innovation is the "first driving force to lead development" and plays a "core" role in China's modernisation. In a study session of the CPC Central Committee in January, Xi has called for a “new whole of nation” approach to address “chokepoint” technologies such as semiconductors.

In his explanation of the reorganization to China’s National People’s Congress, State Councillor Xiao Jie said that “facing international sci-tech competition and external containment and suppression, China needs to further smooth its leadership and management system for science and technology-related work. It will help China better allocate resources to overcome challenges in key and core technologies, and move faster toward greater self-reliance in science and technology.”

So How Is China Doing in R&D?

It is not altogether clear what problem China’s reorganization of Science and Technology is trying to solve. True, the Ministry of Science and Technology presided over the major mishap in the “Big Fund” that was to bring China’s Chips industry at par with the best. It failed to achieve this, amid waste and alleged corruption. Overall, though, China has been rapidly catching up in recent years in R&D capabilities, money spent, research outputs, and number of researchers active in science and technology. More so, there are indications that the quality of outputs of all the research is improving.

According to the OECD, China has now caught up with the average OECD country in terms of spending on R&D as a share of GDP (Figure 1). China now spends 2.4 percent of GDP, about the average of the OECD and higher than the EU, though still well behind Israel (5.6%) and Korea (4.9%), as well as the United States (3.5%).

While growth in R&D spending saw a set-back in Europe and Japan during the COVID year 2020, overall OECD spending continues to growth at 4.5 percent per year thanks to increases in the US and Korea. But China’s growth took the prize at almost double the growth rate of the OECD during 2019-2021. At more than 9 percent growth on average in 2020 and 2021, it easily topped the 7 percent growth target of the 14th Five Year Plan.

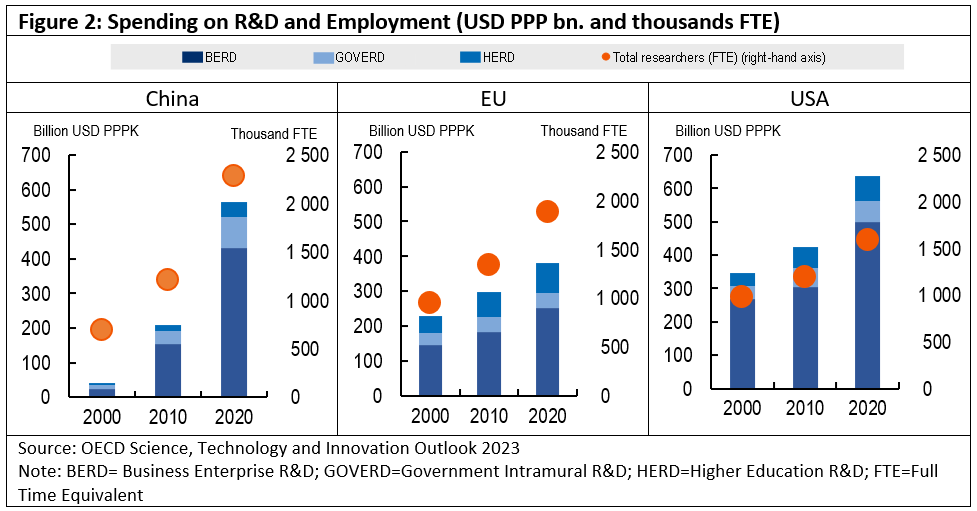

China is still well behind the US in terms of current dollars spent on R&D. However, if measured in comparable prices (purchasing power parity), China’s spending is closing in on the US and has already surpassed Europe. Adjusting for purchasing power makes sense, as researchers in China are, with the exception of the very top, cheaper than in the OECD. China has almost doubled the number of researchers on a full-time equivalent, and now has more researchers than the US and the EU.

As in other countries, the bulk of China’s R&D spending is done by companies (“BERD” in Figure 2). China’s direct government support for business R&D is modest, about 0.13 percent of GDP, only a bit more than half the level of support that OECD countries provide on average. China, though, has a generous additional source of finance, the “government guided funds” such as the “Big Fund” for Semiconductors.

As of the first half of 2022, China has established a total of 2,050 of such funds, with a fundraising target of about RMB12.8 trillion and a subscribed amount of about RMB 6.39 trillion, or almost USD 1 trillion. CSIS, a US based think tank, estimates that total government support for industrial policy, a broader concept than R&D, adds up to some 1.5 percent of GDP, 3 times that of Japan, and 4 times that of the US.

While still modest, China saw rapid growth in the share of government “intramural” spending (GOVERD in Figure 2). This reflects China’s strategy to direct more funds to basic research to be done in National Laboratories, of which China currently has 20. The US has 17 national laboratories under the Department of Energy; in addition, it has some 350 federally funded research laboratories across the whole administration. The numbers are hard to compare though: China’s Academy of Sciences alone has 116 institutes under it.

The quality of research done in China has often been a concern. Indeed, the failure to produce the highest end semiconductors has been a poster boy for the argument that China’s R&D is subpar. Things are changing rapidly, though. The 2022 Global Innovation Index of WIPO, a ranking of innovation capabilities based on 81 sub-indicators, but China at rank 11, up from 37 in 2009, the first edition of the rankings. This is still behind the United States (rank 2), Germany (8) and Korea (6) but already ahead of Japan (13) and France (12).

China has been rapidly catching up in quantity and quality of scientific research, according to the OECD (Figure 3). In 2019 China surpassed the EU in total volume in 2019, and in 2020 it surpassed the US in the number of the top 10 percent most cited papers, an indicator of the quality of the publications.

Some believe China has already taken over from the west in most leading technologies. According to the ASPI’s (the Australian Strategic Policy Institute) Critical Technology Tracker, China is now leading in 37 out of 44 technologies that ASPI is tracking, covering a range spanning defence, space, robotics, energy, the environment, biotechnology, artificial intelligence (AI), advanced materials and key quantum technology areas. The US leads in the remaining 7 technologies (the EU is represented by individual countries, so does not make the top). The ASPI research focuses on the past 5 years, which eliminates high citations based on older, “classic” publications that may no longer be at the cutting edge of science, but still receive high citations. If you want, it tries to measure dominance in state-of-the-art research.

The quantity and quality of patents filed by Chinese entities has also been rising steadily. In 2022, China became the top filer in the PCT patent system of the World Intellectual Property Office (Figure 4). PCT patents are enforced in all treaty countries, and are generally seen to be of higher quality than domestic ones. Domestically, China filed more than 1.4 million patents in 2022, but less than 7 percent were filed internationally, compared to 45 percent of US patents, and 70 percent of Germany’s. The rejection rate of international filing is also still lower than that of leading OECD countries, suggesting that further improvements can be made.

Signs of Decoupling?

Th growing geopolitical tensions will cause headwinds for China’s innovation agenda. The US measures on semiconductors are perhaps the most visible element of these headwinds, but below the radar other worrisome developments are under way. First and foremost, some decoupling is becoming apparent in scientific cooperation. According to OECD numbers, joint papers between US and Chinese scientist has taken a sharp downward turn in recent years, after decades of growth. Chinese cooperation with EU researchers is not yet down, but has been levelling off in recent years, and has always been well below US-China cooperation.

Decoupling of scientists also seems to take hold, at least between the US and China. In the US, almost a fifth of the STEM workforce is born abroad, and almost half of those with a doctorate. About a fifth of those are from China. China and India also make up almost half of foreign-born students in the United States, and many of them stay on after graduation. This may now be changing. The OECD notes that in 2021 China saw a net inflow of scientists, and the US saw a net departure of them. Though again COVID no doubt plays a role, policies such as the now discredited “China Initiative” of the Trump administration may have led many Chinese scientists to conclude it was better to return home.

The numbers are not yet dramatic: China’s net inflow amounted to 3000 researchers from abroad in 2021, presumably most of them returning Chinese. This number pales in comparison with the millions of STEM graduates and hundreds of thousand PhDs in the making in China. But is a turnaround from the past, when the US was capable of attracting scientists from around the world, including China. And those that have spent part of their career abroad are likely the more skilled ones.

A second major factor is a shifting tide in Foreign Direct Investment. Long a powerful vehicle for technology transfer to China, the engine is sputtering. True, overall numbers are still impressive, but most FDI is now done by companies already established in China to expand their ongoing business. Moreover, a considerable amount of “foreign” investment is rather Chinese—repatriated profits or fundraising by foreign branches of Chinese companies. Without doubt, recent numbers are tainted by the effects of COVID-19 and its aftermath, but the sharp decline in the number of greenfield investments in China that the IMF has signaled do not bode well. Moreover, China is particularly vulnerable to the geopolitical and strategic risks the IMF defines in its latest World Economic outlook.

Surveys of the European and US Chambers of Commerce in China companies have for now a “wait-and see” approach on investment in China, in response to COVID, the geopolitical tensions, and the general business climate in China.

According to the 2023 China Business Climate Survey, released in March by the American Chamber of Commerce in China (AmCham China), only 45% of the surveyed American companies regard China as their primary or among their top three investment destinations, compared to 60% the year before. Some 55% reported to put investment in China on hold or reduce it in 2023.

Party Leadership

How will putting a dedicated Party Commission help China’s research and development? Officially, the committee serves “to strengthen the Party Central Committee's centralized and unified leadership over science and technology-related work.” One purpose could be to better coordinate the work among the various layers of government by means of Party Decree. This could help in reducing waste and duplication.

Indeed, one challenge that China has been facing is that it does not have one industrial policy, but many, as the World Bank and the Development Research Center documented in a 2019 report. Each province and municipality pursues its own goals, with its own tax incentives and its own “government guided fund.” This results in too much money pursuing the same ideas and the same talent, and on a political timetable to serve the local leader’s next promotion. Ironically, this results in a relatively short-term focus of government funding—the opposite of what should be the case, namely government providing long term funding for long gestation research. A further spill-over of this is that top researchers keep moving around in pursuit of bigger funding and pay check. Better, Party-led coordination could bring some needed discipline among local governments.

At the same time, politicians are not known to be great scientists, or even great in selecting the promising projects that deserve state support. Fair enough, the National Science and Technology Advisory Committee will advise the party commission, but the big decisions will still be made by the Party.

Some of the most successful programs to promote science and technology is the US’ Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA. DARPA can take at least partial credit for technologies as diverse as Moderna’s covid-19 vaccine, weather satellites, GPS, drones, stealth technology, voice interfaces, the personal computer and the internet, according to the Economist.

DARPA is designed to keep politicians as far away as possible from decisions on which project to back. The program managers, top specialists in their field, are selected to serve one term only, to bring in new ideas, and avoid awarding money to the same old ideas. They are also meant to stay away from vested interest of existing ministries and minimize the bureaucratic hassle that comes with many peer-review based funding channels. It is also meant to produce new stuff, not produce more scientific papers. And since DARPA is set up to take big bets on promising technologies, it is also tolerant of failure.

In some ways, an agency such as DARPA would complement well China’s core strength—its manufacturing base. China has been great at acquiring scientific inventions from elsewhere, and making them better and cheaper than anybody else, as Dan Wang, a technology analyst at Gavekal/Dragonomics argues. In the process, China’s entrepreneurs solve numerous problems, which in turn deliver a constant stream of new ideas, and new patents.

Finally, increased party scrutiny of R&D could even discourage innovation. Creating new technology is inherently risky, and taking risk with the Party looking over one’s shoulder may be a little nerve wreaking. Also, as the “Big Fund” shows, there is a fine line between a wrong bet on technology and corruption, something that the CPC is particularly sensitive to. Finally, devolving implementation responsibilities on some of China’s technology development back to the line ministries seem to invite the vested interests that a more centralized approach through the Ministry of Science and Technology was meant to fix.

Time will tell whether China new set-up will work. What is certain is that technology will be a major field in which strategic competition will take place. And in some ways, China’s model is now copied by their main competitors, as both the US and the EU have doubled down on industrial policy, the same type of policy for which they maligned China in the past.

Thanks! That last line should (no longer) be there. Will correct.

This paragraph ends in mid-sentence: "The numbers are not yet dramatic: China’s net inflow amounted to 3000 researchers from abroad in 2021, presumably most of them returning Chinese. This number pales in comparison with the millions of STEM graduates and hundreds of thousand PhDs in the making in China. But is a turnaround from the past, when the US was capable of attracting scientists from around the world, including China. And those that have spent part of their career abroad are likely the more skilled ones. Thus, although the additional scientists"