Some thoughts on China’s Two Sessions 2025

Prepare for more policies to come

China’s annual feast of democracy is on its way. The sessions of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) and the National People’s Congress (NPC) took off on March 4 and 5 respectively, the latter being of more relevance for China’s policy agenda. At the NPC, Premier Li Qiang presented the Report on the Work of Government, and the government also submitted the budget report (the “report on the execution of the central and local budgets for 2024 and on the draft central and local budgets for 2025), and the planning report ( the “report on the implementation of the 2024 plan for national economic and social development and on the 2025 draft plan for national economic and social development). Premier Li Qiang’s speech took off an hour before on the other side of the Pacific Mr. Trump made his (quasi) State of the Union address to the US congress, and let’s just say that the former was a bit more substantive and organized than the latter, and a lot shorter!

China’s government has set out an ambitious GDP growth target of “about 5 percent.” This is the same as last year’s and was anticipated in provincial growth target announcements earlier this year, which in turn relied on the guidance from the Central Economic Work Conference of last December. The government’s fiscal targets of about 4 percent of GDP in on-budget deficit adds some 1 percent of GDP in stimulus, and off-budget another 0.2-03 percent of GDP further supports GDP. The government’s 2 percent target for consumer price increases (rather than the traditional 3 percent) seems to recognize the challenge of looming deflation in China’s economy. The government also promised an accommodative monetary policy, including further reductions in banks’ reserve requirements and interest rates, but this is unlikely to deliver a further boost to growth at this stage without a rebound in domestic demand.

Despite the macro and micro policy measures announced, the 5 percent GDP growth target seems ambitious. The IMF (4.6 percent) and the World Bank (4.5 percent) both were less upbeat in their January projections, and the consensus among financial sector institutions was 4.5 percent just before the NPC meeting. The government’s target seems deliberately ambitious: the target is a guide for public officials and the private sector alike, and in the considerations of government, will help turn around the negative outlook of consumers and private investors that prevailed in the past several years. Targets, even if an indicative one such as the GDP target, tend to be met in China (in the past 25 years the target was missed only once, in 2023), so if during the year growth outcomes disappoint, the government is likely to take additional measures to boost growth like it did last year.

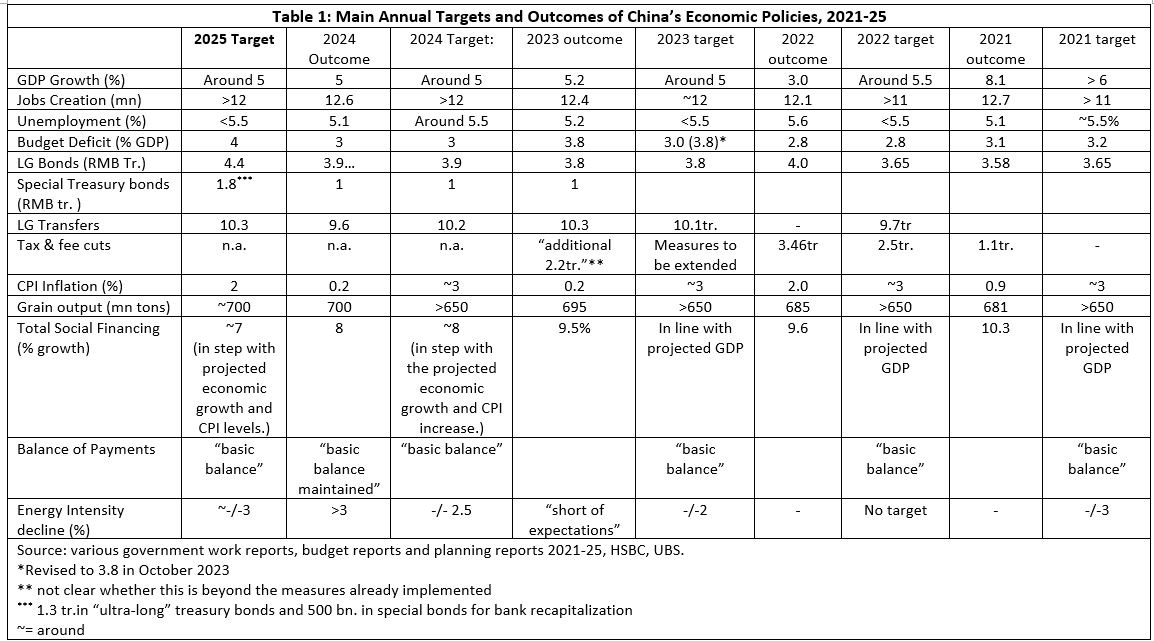

Whether the policy agenda announced at the NPC (Table 1) will be enough to achieve 5 percent of GDP depends in part on an evolving external environment, including the negative impact of Mr. Trump’s evolving and erratic trade policies. For now, the additional 20 percent tariffs will slow down growth, but to what extend is hard to determine. If the 60 percent tariffs that Mr. Trump threatened during his campaign were to come about, the drag on growth would probably too large and further measures would need to be taken. It is likely that Beijing has thought through the scenarios of Trade War 2.0, but whatever happens, it is clear that China’s growth will have to rely more on domestic demand. China’s growing trade surpluses have become an issue not just in Washington, but also in capitals around the world. More domestic demand will help reduce some of the growing tensions and slow the growing trade measures against China, aside from being critical to GDP growth.

Much of the governments contribution to growth will depend on how the fiscal measures announced will work out. The headline budget deficit number of about 4 percent of GDP is only part of the picture. That number is about 1 percentage point of GDP higher than last year’s deficit budgeted last year. The actual deficit last year met the target, but only after additional measures were taken last fall, including issuance of additional bonds, and a redirection of local government bonds towards a restructuring of local debt. For this year, the “ultra- long” government bonds to be issued this year amount to RMB 1.3 trillion, 300 bn. more than last year. The quota allocation for local government bonds is also higher this year, at RMB 4.4 trillion, 500 bn. more than last year (but already accounted for in the 4 percent budget deficit). So, on paper, an additional 1.2 percent of GDP in stimulus will be delivered. The devil is in the detail, though, and more important than the budget deficit number, how the aggregate fiscal deficit evolves is key—but can only be determined after detailed analysis of the budget. The announced reforms in the budget system are a real opportunity for the government to communicate its policy intent more effectively.

A further factor in growth is the Chinese consumer. Despite decent growth rates, consumer sentiment has been in the doldrums for some time, and turning around that sentiment is key for rekindling domestic demand. The work report delivers modest improvements in social protection, but these are probably not large enough to move the needle. More important is the property sector. Chinese people have most of their wealth in property, and a stabilization or improvement in the property sector and property prices is key to helping restore confidence. The work report puts “ensure stability in the real estate market and the stock market” among the priorities for 2025, and announced intensification of ongoing measures, including a new facility at the People’s Bank of China. The report also states that the government will “effectively prevent the risk of default of real estate developers” but whether that means stronger guarantees remains to be seen.

In the medium run, the government can do much more to encourage consumption. Building of stronger social protection, including a more comprehensive and unified pension system, deeper health insurance, and better old age care will reduce the incentive of households to save, and thus consume more. Redistributing some income from rich to less prosperous people would also increase the propensity of Chinese households to consume, simply because poorer segments of society consume more out of their income than richer ones. Gradually increasing the household share in the economy by increasing the contribution of enterprises to the state budget or pensions funds will also support consumption. All that will, however, take time. In the short run, government consumption can raise the overall level of consumption.

Unfortunately, the finances of many of those local governments are in dire straits after the downturn in real estate. Local governments depended for a considerable part of their revenues on the sale of land rights, which in turn depend on real estate development That machine is now broken, and many local governments are deep in debt. They have also started raiding private companies for revenues, which clearly did not add to the confidence of that sector to invest and create new jobs.

The government NPC reports offer some hope for a revamp in local government finance. The program that started last year to convert local government informal debt (of so-called Local Government Finance Vehicles) with local government bonds, which helps a bit in reducing risk and debt service. Furthermore, the central government will increase the transfers to local government by 0.7 trillion over the outcome of last year—though it is the same as in last year’s budget. The proceeds of the local government bonds can this year also be used for clearing payments arrears of local governments, which re-emerged after COVID, and which have drained the liquidity of suppliers to government, and left government workers underpaid. Finally, the government work report promises to make progress on devolving the consumption tax to local governments, which would add about 1 percent of GDP to local government revenues. It will not be enough, though, and progress on the fiscal reforms announced at the 3rd Plenum of the party’s 20th Central Committee is key to shore up local government in a sustainable manner.

Aside from consumers, the other engine of growth that has been stuttering in recent years has been private sector investment. Since mid-last year the government has implemented a charm offensive in an attempt to restore confidence of private investors. This confidence was badly shaken by the regulatory crackdown on internet platform companies, in addition to the “three red line” policies against overleveraged real estate companies. Since last year, the tome has changed, and the government in its work report again assured the private sector that the “two unwavering” (unwavering support for the public sector and the private sector) remains in place. It is indeed in China’s interest to do so: BYD, Huawei, Alibaba and Tencent, and now Deep Seek are all private companies that brought about the breakthrough innovations that Xi Jinping sees as critical for China’s “high quality productive forces” for future growth.

On February 17 this year President Xi Jinping met with these companies and other private sector hi-tech companies to assure them of government support—as well as telling them to contribute to China’s development. In a meeting of President Xi with the delegation form Jiangsu along the side of the NPC, Xi invoked the “spirit of the February 17 meeting” which reinforces the notion that the private sector is welcome in today’s China. A range of support measures for the private sector, some existing and some new, were also included in the government work report. Moreover, further SOE (State Owned Enterprise) reforms were promised as well. Whether this will turn the tide on private investment remains to be seen: one of the key challenges in China’s economy is that increasingly private companies find themselves in direct competition with SOEs in sectors that are of no particular strategic interest to government. Leaving those sectors to the private sector would mean real and meaningful support for the private sector.

On tech, the government has put its money where its mouth is, though. During the Two Sessions, the NDRC announced the establishment of the ‘National Venture Capital Guidance Fund’, a 1 trillion-yuan ($138 billion) government-backed fund aimed at further supporting AI innovation and other high-tech industries such as quantum technology, semiconductors, and renewable energy. In learning from past mistakes, the NDRC stated that this was to provide long-term, patient capital to promote new technologies. In the past, large amounts of government guided funds were not effective because of the relatively short investment horizon the government imposed on these funds. The larger of the funds, the “big fund” for semiconductors became in the end better known for waste and corruption than for the innovations it produced.

Thank you. I always appreciate reading your comments on China’s policies.

Hope China’s policy makers eventually fix the social welfare and pension system to make it more equitable, and work out a better way to fund local government spending while managing moral hazard.

Perhaps in a future article, you might consider whether China’s economy has been suffering from a kind of liquidity trap and significant “shock and awe” levels of government spending (whether consumption or investment) is needed.