I had the pleasure to make a few trips to China in recent months, and in many respects it was a joy to be back, visit old friends in government and academia, and enjoy the clear skies in Beijing and Shenzen, no doubt partially due to the astonishing increase in electric vehicles on the road. In between my first trip (may) and my last (July) the mood with respect to the economy noticeably changed, though. Whereas the first couple of months promised a vigorous recovery after the dismal performance of 2022, the recovery seems to be petering out. The causes and consequences of the slowdown were hotly debated among the people I saw, and in conferences and media in China. Clearly, not everybody agrees, either on the diagnosis, and especially on the remedies the government should put in place.

This posting contains some of my reflections, and (anonymously) is based on the thoughts of many people I met. Apologies for the length, but there was a lot to digest!

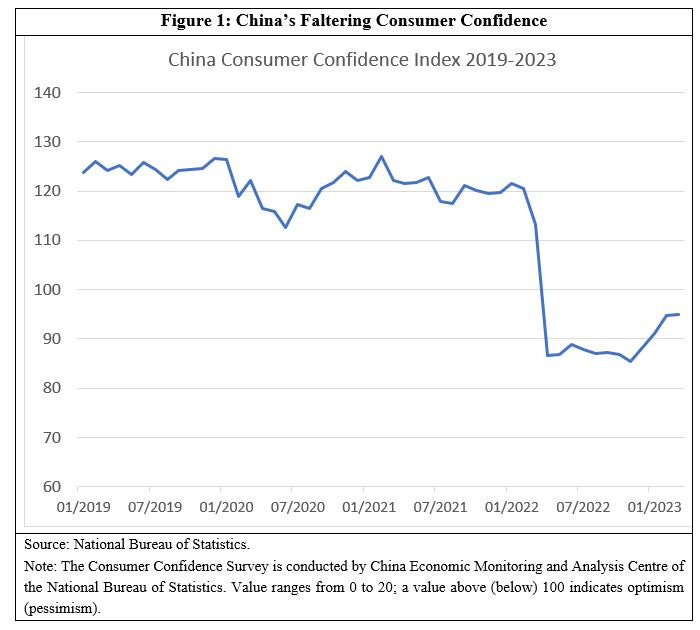

China has had a challenging exit from its zero-COVID policy. Whereas the first quarter of 2023 saw a sharp rebound of gross domestic product (GDP) growth (9% on an annualised basis), this fell to 3.2% in the second quarter—still respectable in the global context, but less than what many have expected. Though the government’s modest indicative target of “around 5%” is likely to be met, private forecasters have been downgrading their optimistic forecasts in recent months. The government is increasingly concerned with the consequences of the slowing economy, perhaps best epitomised by the rising unemployment of 16-24 year olds, which is now at a record 21.3%. Meanwhile, producer prices are falling and real estate prices have weakened. Taken together with demographic decline, high debt levels and faltering productivity growth, some even raised the spectre of “Japanisation” of the Chinese economy, or a balance sheet recession.

Much of China’s economic troubles were policy induced. China’s zero-COVID policy turned from boon to break. The policy was successful at first, with the economy rebounding strongly in 2021 at an 8% growth in GDP. However, the highly infectious Omicron variant changed the equation. Coupled with a growing number of lockdowns and increasingly restrictive measures on mobility, they had slowed the economy to a low 2.2% growth. The sudden exit from zero-COVID in December 2022 provided some initial rebound in household consumption, particularly in services (domestic tourism) but this petered out in the second quarter of 2023. The damage done to jobs creation has been large: according to Xing Ziqiang of CF40, a Think Tank, in the years before the pandemic, the service sector created 10 million new jobs each year, absorbing a large number of graduates. During the pandemic, it created just over one million jobs per year.

A second break on growth came from the property sector. The sector had been a major driver of investment demand since the 2008-2009 global financial crisis, but it had also increasingly accumulated debt and in the eyes of the authorities become a source of risk for financial stability. “Housing is for living in, not for speculation” became the policy mantra often repeated in party documents. To contain the risk, the authorities intervened with the “three red lines” policy in 2020, which effectively limited credit to property developers. When advanced sales as substitute finance dried up during the COVID-19 pandemic, key developers ran into financial problems. This triggered a sharp drop in property sales, new construction starts and land transactions. In turn, this impacted local government finances, which had relied increasingly on land financing. While measures to stabilise the sector seem to have halted the decline, the recovery is wanting, and is likely to drag down the economy for some years to come.

A third headwind for growth is the confidence of the private sector. The clampdown on internet platform companies of the past few years along with the perception that the current administration favours state-led development over the private sector has shaken the confidence of the latter. In addition, diminishing growth prospects and ample production capacity amid sagging demand has also reduced the need to invest in new capacity. As a result, private investments have been shrinking and have become a drag on growth.

Foreign investors face particular challenges in the new era. Aside from the COVID restrictions, they have to manage an environment that has been dramatically changed by the cybersecurity laws, amendments to the anti-espionage laws, growing presence of the communist party in foreign invested firms and the possible fall-out of great power competition. While total foreign direct investment (FDI) numbers held up quite well in 2022, the first quarter of 2023 saw a sharp decline. Moreover, the nature of FDI is changing, with more FDI concentrated in big firms, and smaller firms holding off for now. A growing share of FDI coming from Hong Kong and Singapore, according to a study done by the Rhodium Group, indicates that these funds are in reality Chinese firms repatriating offshore funds. The outlook of foreign investors in China has been increasingly subdued as the regular surveys of the European and US Chambers of Commerce in China demonstrate. Some have called it quits.

Efforts to stimulate the economy are constrained by the high levels of debt, in particular of local governments and households. According to the Bank for International Settlements, total debt to GDP reached close to 300% as at end Q3 2022, a level that exceeds that of most advanced economies and all emerging market economies, and more than double that before the global financial crisis. Of that debt, household debt to GDP is now about 60%, which equals the household share in GDP. Government debt is now some 55% of GDP, but when including the debt incurred by local government financing vehicles (LGFV), it is over 100% (IMF Article IV 2022, Table 5).

Debt of non-financial corporations saw more modest increases in the past 15 years, especially if corrected for the debt of LGFV, which is included in the statistics for corporations. The central government still has abundant capacity to take on additional debt, even though the policies to support the economy through COVID-19 has eroded the government’s tax base. It has also kept its deficit at a conservative level of about 3%, similar to the now discarded Eurozone criteria, which is not necessarily appropriate for China’s economy.

A final headwind for China’s growth is the world economy. China’s exports did very well during COVID, in part because the zero-COVID policy succeeded in reopening the economy while most major economies were still struggling. Since 2022, however, the turn in monetary policies of major economies towards tightening has led to a slowdown, affecting China’s exports. Export values were down 12.4% (year on year) in June 2023, in contrast to the 30% increase in both 2021 and 2022, according to UBS, an investment bank. In real terms, exports still grew by a modest 3.7% in the first half of 2023, though, according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics.

Growing Policy Concerns

The slowdown in growth has raised concerns of the authorities, but they are as of yet falling short of an all-out stimulus. Rather, the July 2023 Politburo meeting on economic work in the second half of 2023 reiterated the “Proactive fiscal policy and prudent monetary policy” phrase already included in the report of the Central Economic Work Conference of December 2022. The slowdown was, according to the readout due to “new difficulties and challenges, mainly due to insufficient domestic demand, difficulties in operating some enterprises, many hidden risks in key areas, and complex and severe external environment”. The solution lies, according to the Politburo, in restoring confidence, promoting domestic demand, stimulating innovation, speeding up the construction of a modern industrial system and “high quality” growth, and focusing on emerging industries such as electric cars.

The sustained emphasis on “high quality growth” signals that the authorities are not ready for an all-out stimulus. “High quality” is shorthand for the growth that the economy can achieve without additional policy stimulus and part of Xi Jinping’s New Development Concept. The concept recognises that the relentless pursuit of growth of the past has created inefficiencies and wasteful investment. It inspired measures such as the “three red lines” policy in real estate, and fed central government reluctance to stimulate the economy. However, the readout suggests that several measures to revamp growth are in the pipeline, including measures to address local government debt (possibly through a debt swap similar to the one implemented in 2015), an acceleration of local government bonds issue, which would open up financing for infrastructure, and measures to promote consumption, including the recent decision to extend the tax credit for electric vehicles. Much of the revival in growth, though, will have to come from the private sector.

Re-engaging the Private Sector

The authorities have demonstrated renewed love for the private sector. A document jointly issued by the Central Committee of the Communist Party and State Council pledged to make the private economy "bigger, better and stronger" with a series of policy measures designed to help private business and bolster the flagging post-pandemic recovery. The private sector has become the mainstay of China’s economy since reforms started in 1978, currently making up some 60% of the economy, 2/3 of investment and almost 90% of urban employment. In an orchestrated public relations campaign, entrepreneurs such as Tencent’s Pony Ma welcomed the new government policy direction.

Officially, the rights of the private sector have been recognised since Jiang Zemin’s “three represents” and the inclusion of private property in the constitution. Prior to that, Deng Xiaoping’s “cat theory” had given the blessing to the private sector after decades of state planning. At the same time, the “basic economic system” considers the public sector as dominant so the private sector is acutely conscious of changes in political winds as evidenced by the crackdown on the tech sector and the possible implications of the “Common Prosperity” strategy and “New Development Philosophy” launched by Xi Jinping. More broadly, the political changes in Beijing, growing focus on national security, Xi Jinping’s consolidation of power and increasing dominance of party over government have created a less predictable environment for the private sector despite the authorities’ objective of “rule by law”.

Xi Jinping had tried to reassure the private sector on the sidelines of the “Two Sessions” this spring. In a meeting with the private sector he had assured participants of the “unwavering support” for the private sector. The “two unwavering” is Party speak for the support of both the public and private sectors which was yet again pledged in the Central Committee/State Council (CC/SC) document in support of the private sector. Premier Li Qiang followed suit in July by meeting tech entrepreneurs and pledging support for the “platform economy” previously hit by the regulatory crackdown. The long-pending investigation of Ant Finance, whose aborted IPO in 2020 had set off the regulatory crackdown, was finally concluded, with an affordable fine, signalling the end of the regulatory rectification.. However, much of the initial boost to stock market prices of the big tech companies was reversed when the Cybersecurity Administration issued draft regulations that would limit the time China’s youth can spend online.

The CC/SC document itself promises lots of measures to support the private sector, some old and some new. A document issued by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) has followed up with detailed support measures While a better legal and policy environment is important for the private sector to regain confidence, the document also reiterates measures against anti-monopoly, non-market behaviour and corruption. It also promises guidance for the private sector, with the word “guide” appearing 22 times, and refers to the “traffic light” system for private investment, first proffered in the context of the tech crackdown to control the “excessive expansion of capital”. In the end the proof of the pudding is in the eating and over time, the government’s track record of decisions will be decisive for a return of confidence of the private sector. A good indicator of the success or failure of government policies is in the amount of capital fleeing the country and number of millionaires planning to leave.

Boosting Consumption

A second plank in the government’s strategy to counter the slowdown is to ramp up domestic demand, in particular consumption demand. This is hardly new as it is an integral part of the “dual circulation” approach to make China less dependent on foreign demand. That objective dates back to the days of the Hu/Wen administration when then Premier Wen Jiabao cautioned that “the biggest problem with China's economy is that the growth is unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated, and unsustainable”.

Since then, China’s household consumption has increased as a share of GDP, but only slowly. The share was 35% in 2008 before climbing to 39%, in 2019, only to fall back to 38% during the COVID-19 epidemic. This is of significance for not only China, but also the global economy: for now, China’s consumer market is far less important than its weight in world GDP suggests. Whereas China’s GDP now approximates ¾ that of the United States, its consumer spending is only 40% of US consumption. Nevertheless, China’s consumption has been growing at a respectable rate, outpacing GDP growth for most of the past decade and a half. The question is whether consumption can save growth, and how.

There are two schools of thought on this point: One says that China’s household share of national income is too low. This is a view propagated by Peking University Economist Michael Pettis and Fudan University dean of the economics faculty Zhang Jun, among others. The other believes that China’s households are saving too much for a variety of reasons, including a weak social safety net, high costs of education and high down payments on property. This is not a trivial difference among academics as whatever is true will determine the policies required to increase the consumption share.

Compared to the United States (and some Latin American middle-income countries like Brazil and Mexico) China’s households’ disposable income as a share of GDP is low—60% versus 77% according to OECD Data for 2019, the most recent available for China (Table 1). However, this share is not too different from that of the EU’s 60%, Japan’s 59%, and Korea’s 55%. As for the sources of gross income, China is at par with the EU and US in terms of share of labour in the economy, so labour is hardly underpaid. The big difference in gross income comes from “operating surplus and mixed income” and property income.

Operating surplus and mixed income reflect income from unincorporated enterprises, including farmers. In the United States Operating surplus and Mixed Income is particularly high in the United States in part due to a friendly tax treatment of such income. In China, this income component is underestimated: China’s statistical bureau underestimates imputed rents—the amount of (implicit) income an owner-occupier receives from not having to pay rent. This could account for as much as four percentage points of GDP in disposable income, and by definition the same amount of consumption

A striking difference in income generated is that China’s households hardly receive any dividends from enterprises (0.4% of GDP), less than 1/10th of what EU and US households receive. China’s enterprises, public and private, have traditionally paid little dividends, despite high operating surpluses and profits (about 20 percent of GDP). Most of that is retained by the enterprises and re-invested. In an environment of high growth this makes sense, but with declining growth rates and declining returns on investment, returning some of those savings to the owners would make sense.

China differs considerably from other countries in how it treats redistribution—the trajectory from primary income to disposable income. While in recent decades China has been building its social security system, the (cash) benefits households get from the system remain modest at 7 percent of GDP, about half of the US, 40 percent of the EU, and 1/3 of Germany’s. Unlike the US, China’s social security system is largely self-financing: premiums paid almost equal pay-outs. China’s taxes on income and wealth remain modest as well and as a result on net hardly any redistribution takes place through the secondary income distribution. This is very different from China’s peers in Table 1, which has major consequences for China’s household savings behaviour.

The really big difference in the consumption share in GDP comes from China’s high household savings rates. China’s households put some 35% of their disposable income in savings, much more than the United States’ 15%, the EU’s 13% and Japan’s 10%. This means China’s households save some 21% of GDP, compared to 11% for the United States, 8% for the EU and 6% for the no longer frugal Japanese. With the exception of the United States, where differences in disposable income explain about half the difference with China’s consumption share, the bulk of the difference for the others is explained by China’s exceptional household savings.

In terms of policy, this would mean that addressing the underlying causes of such high savings would have more immediate results than increasing the income share of China’s households. Strengthening the country’s social safety net, shoring up the pension system, broadening unemployment insurance and deepening health insurance would help in reducing the incentives for China’s households to save. Paying for this through more redistributive (income) taxes on income would put more money in the hands of people that are more likely to spend it.

China could over time increase the household income share in the economy when wage increases outpace GDP growth. In addition, it could use policy to beef up the household income share. Specifically, the paltry dividends that SOEs pay to the government could be increased and used for stronger social security. Undoubtedly, it is also time for private enterprises to pay more dividends. Without major redistribution through taxation and social spending, though, these higher incomes will largely accrue to the rich, which are least likely to spend it.

Balance Sheet Recession?

High debt, demographic headwinds, declining real estate prices and signs of deflation have triggered a debate on whether China is experiencing a “balance sheet recession”. The term was coined at the end of the 1990s by Richard Koo, then chief economist for Nomura, an investment bank, to describe the situation Japan found itself in after the bursting of the financial bubble in the early 1990s. Due to the massive decline in asset prices, Koo argued that households, corporate sector and banks would focus on repairing their balance sheet, leading to a plunge in demand and to Japan entering a decade-long recession. To get out of it, he argued, Japan should embark on massive public spending. Today, China might be entering a balance sheet recession, according to Koo.

Though there are some similarities between Japan then and China now, China seems to be far away from a balance sheet recession. At the time, the blow to Japan’s balance sheets was staggering: The Nikkei Stock Index fell from 39,000 at its peak in October 1989 to 13,000 a decade later; commercial real estate lost 80% of its value; and residential land prices fell by 2/3 between 1991 and 2005 according to BIS data. The collapse happened at a time when Japan was already an aged society, and urbanisation, at some 77% in 1990, had started to slow.

China is in a very different situation today. Though the property sector is seriously affected by the current downturn, the adjustment has thus far been largely in volume terms of sales and construction, not prices. Thus, at least for now, the perceived wealth of China’s households, which has some 2/3 of their wealth in real estate, has barely been affected. The balance sheets of the sector itself has been adjusting, but on both sides—deleveraging was the policy objective that triggered the problems. According to Gavekal/Dragonomics, the balance sheet of the sector has shrunk by some RMB1.7 trillion (about 1.4% of GDP). On the other side of the balance sheet, this was matched by a decline in the sector’s equity of RMB401 billion and a reduction in debt of RMB1.3 trillion, out of a total of some RMB19 trillion loans outstanding to developers. This is only a minor adjustment thus far, not the major shock Japan experienced in the early 1990s, and mainly contained within the property sector. China’s corporate sector more broadly is far less leveraged than Japan’s in the 1980: the debt to equity ratio is about 1.25 in China today, and has been coming down in the past years. In Japan, it was three times as high at the peak of the bubble. Moreover, much of the increase in corporate debt to GDP is due to local government finance vehicles, not “true” corporations.

Koo’s analysis is accurate only where it pertains to China’s economy becoming less and less responsive to monetary policy. Indeed, the (modest) reductions in interest rates have barely had any effect as companies face uncertain growth prospects, have abundant capacity and are yet to discover what the new policy environment means for them. Moreover, they have been deleveraging for a number of years now, in line with the government’s policy. Households face uncertainty from future property prices or completion of any property they may buy. Many have also seen their children, or the children of their neighbours struggle to find jobs. These are hardly conditions for major consumer spending growth.

Rather than a “balance sheet recession”, China’s economic plight can better be described as an “expectations recession”. The July Politburo meeting (and the December 2022 Central Economic Work Conference) recognises as much: “to do a good job in economic work in the second half of the year, we must … focus on expanding domestic demand, boost confidence, and prevent risks”. In such circumstances, a fiscal stimulus could help temporarily, but lasting growth would require deeper reforms to turn around expectations of the private sector and households.

Policies for the Remaining Months of 2023

In the short term, the government is likely to extend support for the property sector by providing liquidity to property developers to allow them to complete the ongoing construction. The language in the readout of the July Politburo meeting suggests as much as it calls for “better meet the rigid and improved housing needs of residents, and promote the stable and healthy development of the real estate market”. The “Housing is for living, not speculation” clause was missing from the readout, indicating a softer stance towards the sector. This could also mean a stabilisation of property prices, which in turn would help repair the shaken consumer confidence, Irrespective, real estate will continue to be a drag on growth for the foreseeable future.

The government will have to address the fallout of the real estate bust for the financial sector. While more bad debts will accrue as the sector adjusts and more developers may default, the government could continue to allow banks to carry bad debts as “investments” on the balance sheet, or they could use the local Asset Management Corporations to acquire the bad debts and finance this with credits from these banks. This “financialisation” of bad debts is likely to be the mainstay of the solution, implying that in the end the depositors pay by means of lower returns on their deposits than they could have had without the bad investments made.

For LGFVs debts, the July Politburo meeting offers some hope as well: “We should effectively prevent and resolve local debt risks and formulate and implement a package of debt plans”, the readout states. A similar approach to the bad property debts may be taken and the 2015-16 playbook could be reused: bank credits to LGFVs in exchange for local government-backed bond, with lower yield, but with more certainty. What central government is trying to prevent, though, is bailing out local governments, a reason for the delay in arriving at a solution.

The July Politburo meeting offers little in terms of promises of a major stimulus. “We should continue to implement proactive fiscal policy and prudent monetary policy” has been the line for some time now and promises little in additional stimulus—which is the much-needed policy for the current circumstances.

If growth is to deteriorate further as the year progresses, a more forceful stimulus cannot be excluded. The most obvious source for such a stimulus would be the central government budget. Unlike local governments, the central government, with debt to GDP below 25 percent, still has the capacity to spend more. In my view, it will only do so, if China risks missing its 5 percent growth target by a considerable margin.

A Reform Package for the Third Plenum

The Third Plenum of the 20th Central Committee scheduled this fall provides an opportunity for presenting a programme of structural reforms that could address some of China’s economic challenges. The unleashing of a “reform and opening up” by Deng at the Third Plenum of the 11th Central Committee in 1978 has set the precedent for third plenums to spell out China’s economic reform agenda.

The Third Plenum of the 14th Party Congress in 1993 introduced the “socialist market economy” and the Third Plenum of the 18th Party Congress introduced a set of measures to shift China’s growth to one led by productivity and innovation, including by designating the market as the decisive force in the allocation of resources. These reforms were only partially implemented, and the Third Plenum of the 19th Central Committee was used not for economic reforms, but for getting consensus on the constitutional reforms that paved the way for Xi Jinping’s third presidential term. It has been a decade since a comprehensive economic reform programme was presented.

On the other hand, Central Committee Plenums do not serve to settle major ideological issues, a role reserved for the National Party Congresses. The 20th Party Congress last fall reconfirmed the primacy of economic development, a priority that was established in 1978 with reform and opening up. According to Xi Jinping’s general secretary report to the Party Congress, “Development remains the main objective of the Communist Party of China (CPC)” and the “New Development Philosophy” will be the main concept behind the country’s economic policy in its quest to achieve a new development pattern, which is balanced, open, sustainable and equitable.

In the meantime, At the same time, Xi Jinping emphasised national security as the basis for economic development. Aside from more traditional elements of security such as food and energy security, national security is increasingly broad in focus and application, in part in response to perceived external threats and in part to increase the control of the CPC over society. The tension between economic development and national security will continue to be a factor in economic policymaking for the foreseeable future. The Third Plenum is an opportunity to spell out how the government wants to marry the two—economic development and national security—if that can be done at all.

China has to overcome several obstacles to the CPC’s primary goal of economic development. Demographic headwinds have become a growing tax on growth. The projected decline in labour force would reduce growth by some 0.7-0.8 percentage point per year. Labour needs to be used more efficiently as well: a quarter of China’s labour force is engaged in agriculture—compared to some 3% in OECD countries. The household registration system and land user rights are holding back the reallocation of labour to more productive uses.

Ageing would also erode China’s high savings, which in turn would lower investments, the main driver of growth since the global financial crisis. Investment efficiency needs to improve, as returns on investment have been on the decline over the past decade. China’s incremental capital output ratio, a measure of investment efficiency, had rapidly increased from 3.3 in 2007 to 7.4 in 2020, and returns on assets have declined in line: private sector returns declined from 9.3% in 2017 to 3.9% in 2022, whereas SOE returns declined from 4.3% to 2.8% over the same period.

Meanwhile, growth in overall efficiency in the use of factors of production (TFP) has slowed as well. Whereas TFP growth in the 1980s-2000 contributed some three percentage points to growth, or about 1/3 of total, in the past decade, this contribution has declined to one percentage point, or less than 1/6th of growth.

Some decline in growth has to do with the less conducive international environment. The general secretary’s report to the 20th Party Congress dropped the notion of an “important period of strategic opportunity” and instead, characterised it as a “period of development in which strategic opportunities, risks and challenges exist at the same time”. Economic decoupling, though not yet apparent in the trade date, is increasingly a threat to China’s development, while US measures on high-end semiconductors could derail a significant part of China’s technology agenda.

The IMF now estimates that, without major reforms, China’s potential growth will fall below four per cent in the coming years. At such levels of growth, China will fall short of meeting its objective of doubling its 2020 GDP by 2035, the end of the first phase of Xi Jinping’s New Era. To turn this around, major reforms are needed, among others:

• Fiscal Reforms. At the core of the misallocation of capital in infrastructure and real estate are the problems with the fiscal system. A growing demand for public services at the local level has not been met with more resources. Moreover, incentives for local government officials remain biased towards growth. Major fiscal reforms are needed, including expanding the tax base to grant a better revenue base for local governments and revisiting the economic functions of local governments and the intergovernmental fiscal system. A carbon tax, property tax and broader application of the personal income tax are concrete options that would restore China’s revenue base over time.

• Financial sector reforms. China’s abundance of savings is likely to decline in the coming decades, more so in the absence of reforms to improve productivity. Lower savings imply that the allocation of those savings would need to improve to keep growth at acceptable levels. Financial sector reforms are key to this and the reorganisation of the financial sector supervisor is a start. The thousands of local banks that have emerged are little more than development banks for local governments, and should be centrally, rather than locally supervised. The sector is likely to see a consolidation in the coming years to weed out the weak banks (most likely by merger with strong banks, if the past is a guide). Cleaning up the debts of local financing vehicles is also critical in the short term, but longer-term reforms to diversify the financial sector and increase returns on investment will require deeper reforms as well, most notably a diversification away from the bank dominated system, and delinking local governments from local banks.

• Retirement age and pension reforms. The decline in the labour force, which has been ongoing for a decade, could be countered by adjusting the retirement age. If China’s workers were to retire like the Japanese, an additional 40-50 million workers would be in the labour force by 2035. Reforms in the pension system could encourage people to work longer while improving the financial sustainability of the pension system; there is also a need to expand the system for migrants and rural areas (the urban and rural resident system).

• Household registration reforms. Urbanisation has been a major driver of growth in the past, but has slowed in recent years. The urban population is now at some 65% of the population, but almost 20 percentage point of this are migrant workers. Some 25% of the labour force is still employed in agriculture, compared to an average of 3% among OECD countries. Further reforms in the household registration system are critical for increasing labour mobility and labour productivity growth.

• Social safety net reforms Providing rural citizens and migrant labour with the same social protection as urban workers would help support consumer confidence and consumption growth, as well as strengthen counter-cyclical policies and wean government off infrastructure investment as the only tool to stabilise the economy.

• State Enterprise Reforms. Even though China will continue to maintain a large SOE sector, there is broad agreement among China’s policymakers that the sector should perform better. The Third Plenum of the 18th Central Committee in 2013 had already decided that better “State Capital Management” should be a priority. Increasing dividend payments from SOEs would be a good start. Divesting non-core activities from SOEs, such as real estate development and tourism would allow the sector to perform better on its core tasks. Reorganising SOEs into non-commercial and commercial, and managing the latter through state-investment companies, would further increase the returns that the State (and the Chinese people) would get from its property.

None of these reforms are easy, and each one cuts into the interest of some groups in society that have managed to block these reforms thus far—be it urban citizens, the relatively well-off, and SOEs. For that reason, a coordinated package of reforms, such as can be approved in the Third Plenum later this fall, will be critical for China’s growth. For each individual element in the package there may be winners and losers, but the package as a whole should increase the pie for all. The Third Plenum will therefore be the first serious test for China’s new economic team.

This is undoubtedly the clearest, most balanced, and authoritatively comprehensive insight on China's present situation. Bravo and kudos. Reads better than anything from Financial Times and Economist, and leaves WSJ, WashPost and NYT in the dust.

Hofman should next write two other critical pieces: (a) Decoupling/Derisking, and (b) Technological Sovereignty In The Era Of Geopolitical Divergence, both in the context of 'Rise Of The Rest' and the socio-economic future of humanity facing 'disparity and climate' challenges.

How we have all gotten to the present global tense situation could have come about from political decision-makers using their 'whack-a-mole' approach. In the case of US-China relations, the G7 leaders and think-tank(ed) players should more honestly consider the following differences between both countries which in turn inform on the universal challenge of how to manage bimodally (bimodal management which tries to solve composite problems by using linear methods to achieve seemingly opposing objectives), furthermore muddied by distorted news reporting in western mainstream media:

1. history and ideology

2. low base vs high base

3. displacement and containment

4. ethnonationalism and tech sovereignty

5. cooperative clean tech